Nature is the source of your business and ours

Together we can unlock opportunities that secure the future of your brewing business.

Want to advance your business? Sustainably? You need enzymes. Whether you’re looking to optimize your processes, innovate your products or reduce your environmental footprint, we help you make a measurable impact. Together.

Together we can unlock opportunities that secure the future of your brewing business.

Which solution best meets your needs? Use our product finder to pinpoint the solution to your challenges. Applications include cereal cooking, separation and filtration, attenuation and more.

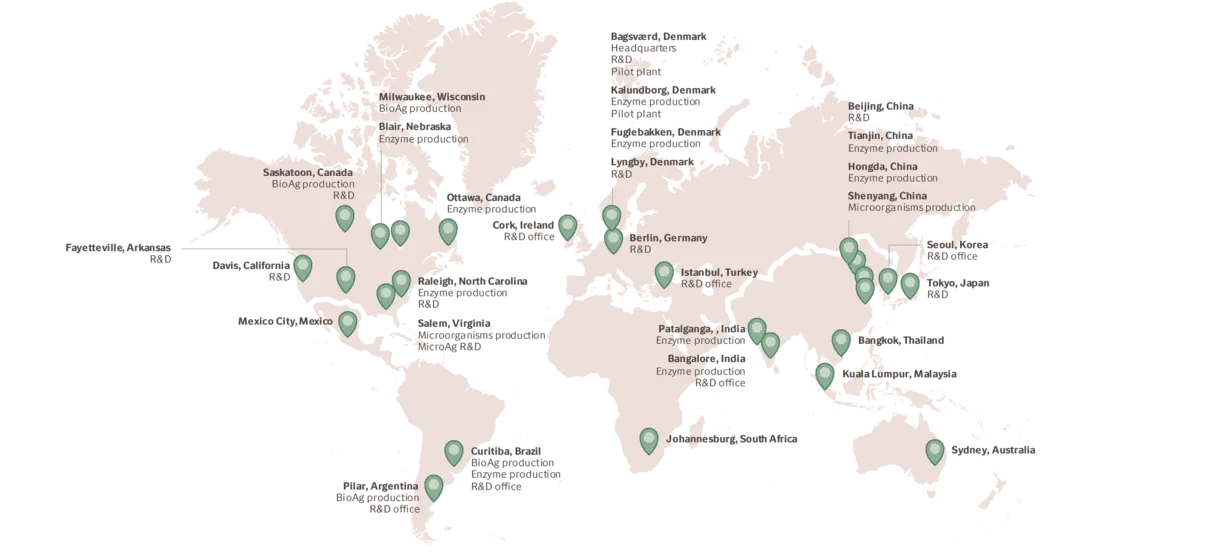

With production facilities on four continents, warehouses all over the world and a flexible, robust distribution network, Novozymes delivers on specification, on time – even in times of crisis. A commitment to serving our customers at every link in the value chain is part of our DNA. And we always work hand in hand with you to meet your needs.

Find out how we helped our customer optimize their process and improve sustainability

Find out how we helped our customer increase sustainability and innovate their product

Discover how we helped our customer increase sustainability

Discover how we helped our customer develop new brewing products

Discover how we helped our customer develop new brewing products

Find out how we helped our customer in Asia-Pacific optimize their process

Find out how we helped our customer in Europe optimize their process

Find out how we helped our customer in Americas optimize their process

Enzymes give you the freedom to find new ways to serve the growing number of demanding consumers looking for new experiences. You can premiumize your offerings, leverage your brand presence in the market and continue penetrating new niche and emerging markets.

Not only does that benefit you – it’s also good for local farming communities, consumers and the planet.

When you work with Novozymes, there’s always someone close by to help you implement and optimize our solutions to fit your needs, conditions and raw materials. You’ll benefit from our large Technical Services centers in China, Denmark, India, Malaysia and the U.S. A variety of online service tools further ensure you’ve got what you need, when you need it.

Our service-minded team of brewmasters, scientists and commercial experts looks forward to advancing your business together.

We regularly update our LinkedIn page with consumer and product insights to help you brew sustainable. Follow us to access white papers and reports, as well as registering our popular webinars.